Experiences of everyday hate in the lives of disabled people: intersectionality & resistance

In this latest in a series of blogs by our PhD students, Leah Burch introduces her research into disability hate crime. Leah has already begun publishing in the field of Disability Studies, see for example her article 'Governmentality of adulthood: a critical discourse analysis of the 2014 Special Educational Needs and Disability Code of Practice' in the journal Disability & Society. Her supervisors are Professor Mark Priestley and Dr Tom Campbell.

Developing discussion around the concept of hate crime presents a welcomed surge of interest in the topic. At the same time, it risks creating a concept too detached from the everyday realities of those experiencing it (Chakraborti, 2016). Ambiguity and confusion surrounding the concept is clear when considering recent figures. In 2016/17, there were an estimated 7,226 ‘disability hate crimes’ recorded by police. In comparison, findings from the Crime Survey for England and Wales suggest that there was an estimated 52,000 ‘disability hate crimes’ in the same year. For me, this suggests a need to go back to basics, thinking about how we define and understand hate crime.

To think about what hate crime means in practice requires deep engagement with those who are experiencing it on a regular basis. This project shifts the focus away from complex academic debates, temporarily, instead gaining insight and knowledge through the experiences of disabled people. The scope of the project is broad in order to allow for these unique insights, yet can brought together by three defining concepts: ‘everyday hate,’ ‘intersectionality,’ and ‘resistance.’

Everyday hate

Hidden behind the few, extreme acts of hate crime broadcast on media headlines, are the vast number of hate incidents and hate crimes that occur within the everyday lives of many people. Hate crimes are not solely committed by extreme ‘bigots’, but by ordinary people in the context of their ordinary everyday lives (Iganski, 2008). Contrary to the popular belief that, for example, no-one really hates disabled people (Sherry, 2010) is an uncomfortable reality; many disabled people experience ‘hate’ on a regular basis. My project centres upon these everyday experiences in order to better understand, and thus challenge, the ordinary yet damaging nature of hate crime.

Intersectionality

Experiences of hate crime cannot solely be explained in terms of disablism, but rather a myriad of identity-based acts of oppression. While there have been important developments in hate crime research that consider the intersectional weaving together of multiple identity constructions (e.g. Connell, 2016; Meyer, 2010), disability has been an excluded characteristic. Thus, this project employs an intersectional approach to researching the complexities of hate crime experiences for disabled people, seeking to unearth the meaning of these experiences in relation to their interacting identity characteristics.

Resistance

The various layers of harm that can be enacted through and by hate crimes are well documented. Less known, however, are the diverse ways that individuals navigate these experiences. Many disabled people have developed intricate means of responding to, and resisting a disabling social world in their everyday lives (see Siebers, 2013). This research taps into these strategies of resistance that are already being enacted in the attempt to share and celebrate them. Doing so, I hope to gain a deeper understanding of how disabled people negotiate their experiences of hate crime, and think about how we can come together as a collective.

Preliminary Reflections

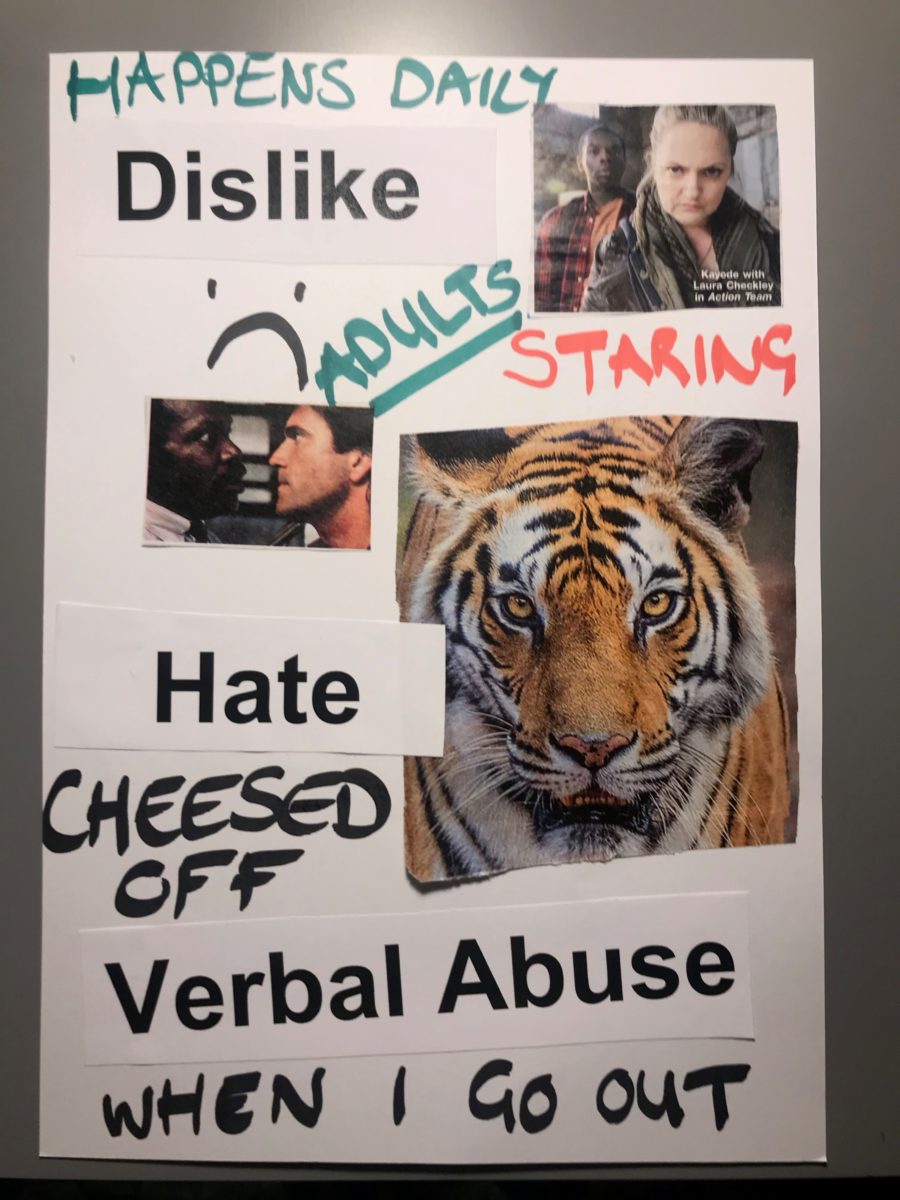

I have recently begun conducting the first stage of my fieldwork. This involves a series of participatory workshops that include general discussion, collaborative concept-mapping, and craft-based activities such as making mood boards.

Violet's Mood Board

I am only in the very early stages of the fieldwork and so it would not make sense to draw too many early conclusions. But what is becoming clear is the value and importance of engaging with the everyday realities of hate crime. The understandings and reflections offered by participants are informative in many ways. They both align to and challenge the academic discourse surrounding hate crime that I had previously been immersed within. They present the messiness and the complexity of hate crime, rather than as a neat category with definitive boundaries. They leave me with more questions than answers as we collaboratively explore the meanings, presence, and forms of everyday hate and hate crime. It is refreshing being immersed within the data, not necessarily knowing what I believe, or what I think, but allowing my own knowledge to be stretched and disrupted through the exciting process of data generation.